From troops to teachers: BVH teachers share their experiences in the military

After his high school graduation in 1993, AP World History and International Baccalaureate History of the Americas teacher Jose Vallejo entered the U.S. Navy. Leaving behind a single mother and a sister in his hometown of San Diego, he was stationed in Norfolk, Virginia aboard the USS Ponce (LP15), hoping to gain an education through the military.

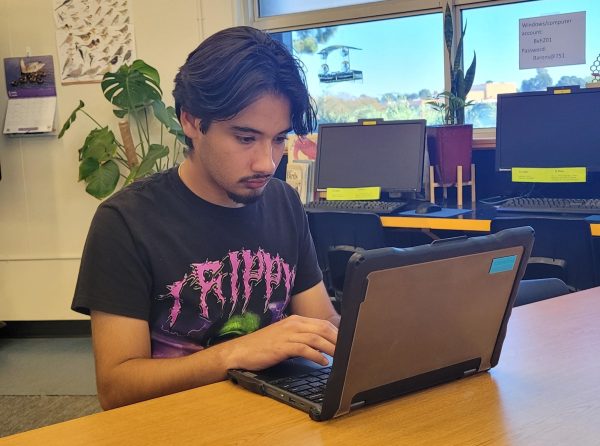

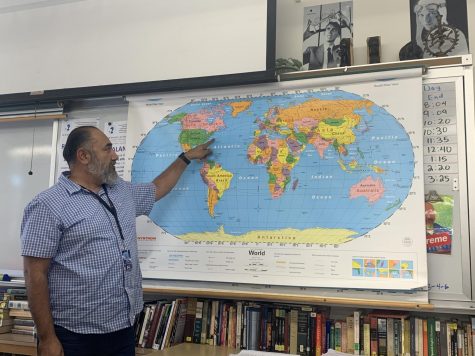

Describing his time in the Navy, History of the Americas and AP World History teacher Jose Vallejo points to a world map in his classroom to illustrate the path his

ship took across the Atlantic ocean. Vallejo was aboard the USS Ponce (LP15) for three and a half years.

“[The most valuable lesson I learned] was that it is possible to accomplish a lot of things, even through self doubt,” Vallejo said.

At 17 years old, senior English teacher Carmen Ramirez-Stokes joined the U.S. Navy despite her mother’s disapproval. Her military service allowed her to travel across the country. She served five years in the Navy, and has continued to experience military life through her husband who currently serves.

“You get to know the different regions and the people that live there. It’s pretty interesting because then you are open to other cultures. Just being able to be around all of those different cultures was very educational,” Ramirez-Stokes said.

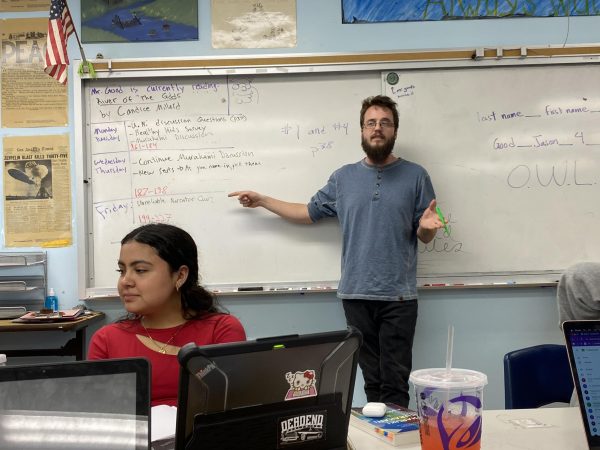

English 9 and English Language Development (ELD) teacher Dennis Perez, Ed.D., grew up in a large family with a military background. He followed in his family’s footsteps, by eventually serving in the U.S. Naval Reserve, the Marines Corps and the Navy. He served eight years, mostly under the Marines Corps.

“Be prepared to serve. You’re not here for yourself,” Perez said. “I love the saying that ‘We protect people that can’t protect themselves.’”

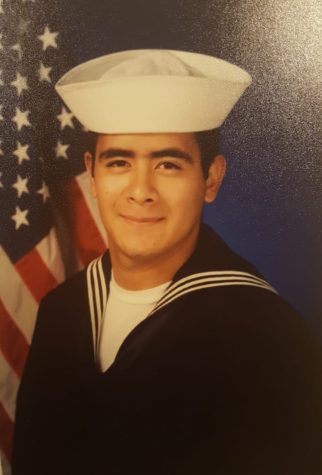

Coming from a disadvantaged background, Integrated Math 3 teacher Richard Silvas joined the military as a way to provide for a family. Although he was often underestimated for his Hispanic ethnicity, he served one year in the U.S. Army and 10 in the U.S. Navy.

“At first you’re like, ‘Oh, it’s just a job.’ But then once you’re in for a while, it’s like ‘this is something that I’m proud of, and my family’s proud of too,’” Silvas said.

At 15 years old, U.S. Government and U.S. History teacher Frank Schneeman dropped out of high school; then, for two years, he worked full time before entering the U.S. Navy at the legal age of 17. He served in the Korean War, before being hired at Bonita Vista High (BVH) where he has taught for 40 years.

As Veteran’s Day approaches on Nov. 11, BVH teachers share their stories of their service in the U.S. military before their teaching career, involving travel, hardships, motivations and what they believe it means to be a veteran.

PERSERVERANCE

BVH veterans expressed that, despite the challenges of being away from home, they preserved through the motivation to reach different goals.

“I [was] definitely homesick [the first year]. I questioned, ‘what am I doing?’” Silvas said. “But it was nice that I kept in contact with my family and knowing that I was laying a foundation for myself and my future family. That that’s what kept me going.”

Saying goodbye to family members for long periods of times proved difficult for the veterans, especially as life continued at home. During boot camp for the navy, Vallejo missed a major surgery his mother undertook which removed one of her legs, and was oblivious to what he missed until he came home.

“I wanted to help, I have a single parent so my mom was my world,” Vallejo said. “I didn’t know until I came back home. My sister didn’t want to tell me; it’s just my sister and I and she didn’t want me to know [while I was away].”

However, there were many different initial reasons to join the military. Many of the veterans expressed how they saw the military as an opportunity for a more accessible college education.

“I wanted to go to college, and I knew I had what it takes to get through college, but I just didn’t know how I would pay for it,” Vallejo said.

The military does provide financial services to veterans who served at least three years, in the forms of the previous G.I. bill, now the Post 911 bill. BVH veteran teachers took advantage of this opportunity to help better secure a future.

“I grew up in a very poor family. My family didn’t have any money for college. We didn’t have any money for food either. There were several times that we went days without eating. So I always thought the military was a good way for me to get a foundation so that I could save up money for college and have the military actually pay for college,” Silvas said.

However, education wasn’t the only push to join the military. For Ramirez-Stokes, the military was a way to travel out of the city she had grown up in.

“Around that time when I grew up in Los Angeles, there was a lot of police violence. The Rodney King riots had just ended in ’92. Half of LA was burned down and it was not a place where I wanted to be or where I could see myself grow into an adult or have children,” Ramirez-Stokes said. “[I was] tired of living in that city. Probably one of the easiest ways to get out was to join the military.”

With these goals in mind, the veterans were able to carry out service in the military for years before getting a college education and establishing careers as teachers.

“I’m just thinking of the fact that I probably would have been at home with my mom for a long time, doing a mediocre job, and then probably not realized that I needed to get out,” Stokes said.

COMMUNITY

Shortly after 1948, when the United States military was first racially integrated, Schneemann first stepped foot onto the ship that he would call home for the next few years. When he settled into his barracks, he observed an array of faces, a kaleidoscope of diverse complexions.

“The military is the best of all the institutions in society for integrating,” Schneemann said. “When you’re in the military, you don’t think about race or anything like that. ‘Me’ becomes ‘us.’ You’re all the same.”

The integration that Schneemann experienced was the first evidence of an emerging sense of community among soldiers, regardless of their appearance or background. This camaraderie spans racial, societal and generational gaps, forging a sense of unity.

“It’s this big melting pot where there are people from the south, from the north, from the west and the east, all in one facility,” Ramirez-Stokes said.

However, the exposure was not limited to the living quarters. Traveling around the world, or even just the country, broadened the worldview of many veterans.

“I grew up in World War Two as a kid, hating the Japanese. I hated them. But when I went to Japan, I fell in love with the Japanese,” Schneemann said. “I really liked them. They were so friendly, honest and nice.”

Acceptance was facilitated by one of the core principles of the military: teamwork. Training for the military was harsh, demanding and allowed no room for defiance. When there was a task to be accomplished, it was all hands on deck; for in action, functioning as a team could be the difference between life or death, success or failure, victory or defeat.

“The military forces you to work with other people. If you don’t, you’re going to be kicked out really soon,” Silvas said.

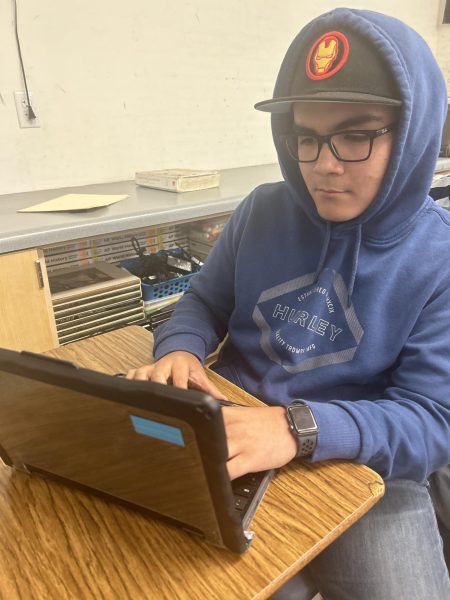

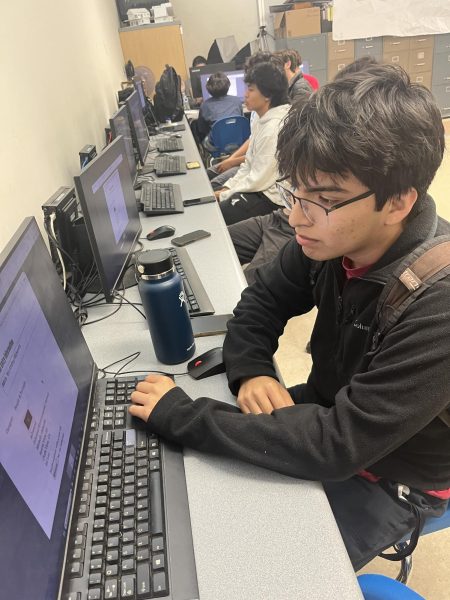

During his training at his Navy boot camp in 1988, Integrated Math 3

teacher Richard Silvas recalls the organization and discipline of the military as one of the most prominent features.

Especially through their training, collaboration would be the gateway to progress. As a cross country runner before his time joining the Navy, Perez was prepared for the physical challenges of bootcamp. Staying in shape was the least of his worries. With that in mind, Perez’s commanders appointed him to train with his fellow soldiers.

“The Marines have a special relationship,” Perez said, describing the bond between other Marines and war doctors like himself. “They call us ‘docs,’ they come to us for medical and emotional support. Every Marine that I run into, I tell them I’m a ‘doc,’ we have a long conversation about each other’s experiences.”

One experience of Perez’s in particular exemplifies the importance of cooperation in the military. During his time in bootcamp, his commander had taken him and his fellow soldiers on a 15 mile hike to the top of a mountain. By then it was nighttime, and the soldiers had set up their tents, exhausted from a long day and ready to go to sleep. However, within 10 minutes, their commander ordered them back down the mountain.

“He yelled at us to pack up our tents and go down the hill; you never know when the enemy is going to attack,” Perez said. “And it was a valuable lesson. You don’t get those kinds of training anywhere else. We made it through because we did it together. There was nobody that wasn’t going to make it through that day.”

Whether it’s placing American flags on the gravestones of fallen veterans, having a barbeque with military friends or reconciling mutual past experiences, their time in service binds those in the military, regardless of if they served in the same time or place.

“You’re sitting there, preparing for something that could be really, really dangerous and you’re holding space with your friends emotionally,” Perez recounted. “And you would think that we’re all big and tough, but these are guys who open up and start shedding tears about their loved ones back at home. You start to think ‘yeah, this is our family right here.’”

DISCIPLINE

Discipline proved to be a large part of the journeys these veterans had during their time in the military. Many believe that the military instilled a value of discipline, in that it forged maturity during their time, especially for those who started young.

“One of the motivations [I had to join the military] was to leave home and grow up,” Perez said. “Sometimes you need your space, you need to be able to flap your own wings. It was my time, and even though my dad encouraged [my siblings and I], I was ready to leave my home to grow up, to be an adult myself and move away from the routines of a large family.”

Perez sought maturity through the strict structure of the military, which he believes are in place primarily to develop the discipline he gained.

“We were just raised with the values of serving. I think [the] primary goal for us joining the military was to have us gain discipline and adult skills that would help us be successful in life. It just happened that I like the military life,” Perez said.

Similarly, Vallejo expressed the initial surprise he felt when he realized how the military had shaped him into a more mature person after high school. Vallejo entered the navy at 18 years old.

“[I had] just graduated high school, and after six months I was driving a navy ship in the Mediterranean Sea right off the coast of Greece. My thought was, ‘Wait, the military trusts me with a 300 million dollar navy ship? A few months ago I was hanging out in TJ,’” Vallejo said.

The veterans share the idea that the discipline instilled by the military is transformative; Schneemann, for example, describes the drastic change in his life before and after joining.

“It was different. You go from being an inner city street kid, what I was, and go into all this regimentation and marching and marching in the freezing cold in the Great Lakes, Illinois,” Schneemann said.

Schneemann credits his time in service for not only a transformation of identity, but also the development of crucial skills in independence and self-discipline.

“The Navy made me a man. They taught me how to do my own laundry and they told me to follow rules and regulations I didn’t ever have to do before. Living in the inner city, you live on the streets, you don’t follow any rules,” Schneemann said.

However, the discipline these veterans learned followed them after their service. Even after their retirement from the military, they find that their current actions reflect what they learned. In Vallejo’s case, the discipline curated in his time in the navy played a role in his college education following his service.

“I kept the same motivation that I had in the military. In fact, I finished a bachelor’s degree in three years [with the aid of military funding],” Vallejo said.

For Perez, this discipline has followed him to the classroom he teaches in now. He expresses how his sense of self discipline helps guide his teaching with younger students, who are still maturing.

“I have to balance my own personal discipline with the understanding that I [have] a lot of ninth graders [as students] and they’re just in the journey of becoming a disciplined person,” Perez said.

While Perez’ reflection on his own discipline influences how he interacts with his freshmen students, Schneemann’s experiences with discipline influence how he interacts with his senior students, in a different way.

“It makes me look at seniors more as adults than kids, because I keep thinking about what I was doing when I was 17 or 18; I was going to war,” Schneemann said. “I can’t [help but] tend to look at seniors as more adults than kids.”

Sometimes we under-value and under-appreciate those who have served. We don’t know why they joined or what they did. If you know a veteran, say thanks for what they’ve done.

— IB History of the Americas and AP World History teacher Jose Vallejo

Locations of Deployment of BVH Teachers

SERVICE

Although their military experience is a memory of the distant past, succeeded by their families, careers and new experiences, the BVH veterans will never forget what their years of service symbolized. For, without their time in the military, many of them do not believe that they would be the same person that they are today.

“I haven’t thought about the military in a long time,” Vallejo reflected. “Many veterans don’t like to talk about their time in the military. We’re very modest because it’s a sacrifice we made willingly, not to brag.”

The sacrifice that Vallejo speaks of is not only one for the betterment of their families’ lives, or even their own. But it is also a sacrifice made on behalf of their country.

“I feel like I’ve done my duty when I should have. I love America. I really do. I know a lot of teachers think it’s corny, but I love America to the core of my soul,” Schneemann said. “I think it’s the best place in the world for people that are put down and need to be uplifted.”

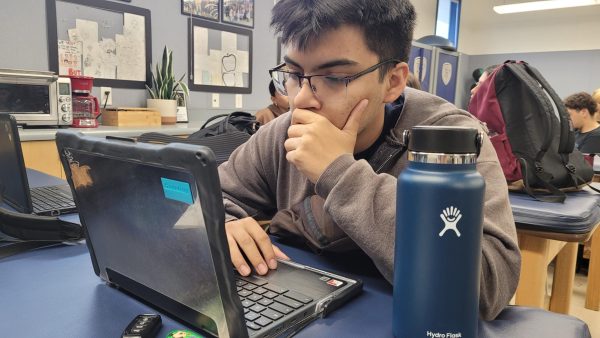

In Dec. of 1964, Government and History teacher Frank Schneemann shared a meal with a Japanese woman when he was stationed in Japan. Before traveling to Japan, Schneemann disliked the Japanese, due to their portrayal in the media at the time. However, after his visit, he gushes about his affinity for the Japanese people and their culture.

While these veterans are proud to have served their communities and have gained much from their vibrant years in duty, there are moments when they have had to grapple with the unsettling reality of war.

“I was spending the night on an asphalt, barely with a sleeping bag, looking up at the stars, and I thought about something my commander had said earlier: ‘Listen, I know no one likes to kill. But when you have the whole country depending on you to save something, and your enemy’s shooting at you, instantly, you change from worrying about shooting someone, to worrying about protecting the people around you and your country,’” Perez recollected. “Before that, I didn’t really think that I was going to be able to take a gun and defend.”

It is those ideals and people that these veterans swore to protect, that motivates them to fight stereotypes about their duties. Seemingly, those in the military appear to be preoccupied with plans of attack and violent tactics, but this perception does not account for the depth and dimension of the duty that soldiers carry with them.

“The majority of Americans think of us as warmongers, but I don’t see us as warmongers. I see us as keeping the peace,” Silvas said. “The military is just a big, heavy hand that lets the world know ‘Hey, we just want peace. We don’t want to go to war.’”

None of these veterans wanted to go to war and engage in the violence; they wanted to travel, to mature, to learn, not to kill.

And after they served in the military, they longed for another way to serve: teaching. Passing on their experiences and continuing to sacrifice, not in battle, but in the classroom, is how these educators fulfill a sense of duty.

“Just like the military, in groups during math class, you’re talking and having a good time. But there’s a pencil in your hand. You’re doing the math problems, we’re going over it as a group and we’re growing up as a class,” Silvas described.

As veterans, their approach to educating is influenced by their experience traveling across the country and the world, working in a diverse community and perseverance in times of struggle.

“The military embedded a military bearing into my teaching style, meaning that you’ve got to get your job done first, and then you look at having fun afterwards,” Ramirez-Stokes said.

Whether it is through the countless stories they share, the advice that they give, or the lessons that they teach, there remains a simple truth: these veterans may have retired from the military, but the military continues to shape their identity.

“I feel that I bring a sense of discipline and care to my classroom, that I expect from my students,” Perez said. “In being a part of a community, you learn how to care for people. You find the most challenging kids and you learn how to love them. And, in that way, the military has taught me to be caring, loving and disciplined all at the same time.”

In his classroom at the end of the 200s buildings, Government and History

teacher Frank Schneeman decorates his room with photos of his family members and a bust of George Washington. On Washington’s head rests

Schneemann’s cap that references his service in the Korean War.

I am a senior attending Bonita Vista High. Journalism interests me because I believe strongly in the power of words to impact people, and to shed light...

I am a senior at Bonita Vista High and a fourth year staff member on the Crusader. I am now co-Editor in Chief, and previously was News Editor, Features...