Diverse history needs a diverse curriculum

Before the end of Bonita Vista High’s (BVH) first semester, U.S. History, Advanced Placement (AP) U.S. History and International Baccalaureate (IB) History/U.S. History Honors teacher Candice DeVore proposed to the Sweetwater Union High School District (SUHSD) that a new class titled Women’s Studies and History be approved at BVH.

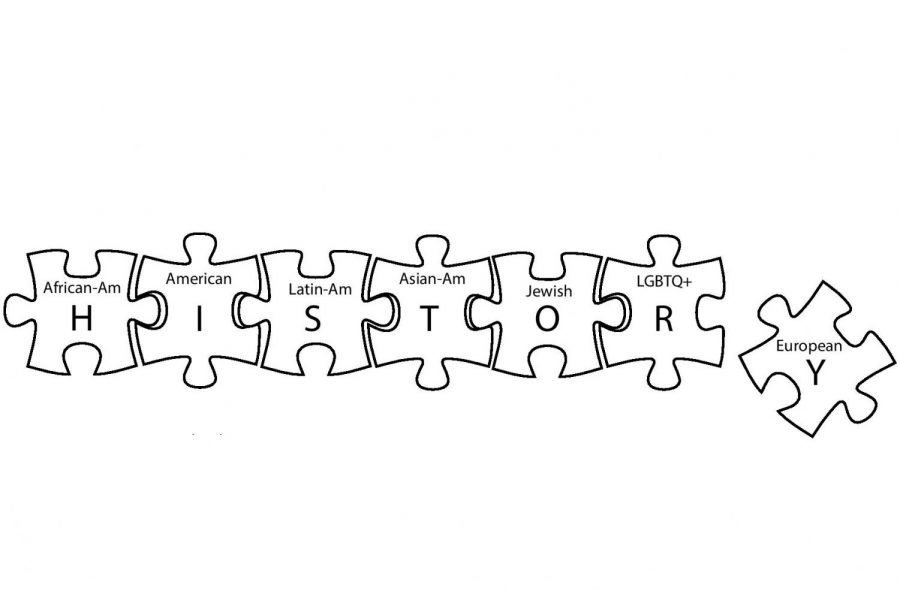

Whether or not this class gets approved and added to the school’s roster, BVH needs more specialized, diverse history classes that resemble the one proposed. Classes that focus on African-American, Latin-American and Asian-American history, among many others, would allow BVH students of all grades to reap the benefits of learning history through more diverse perspectives.

Samantha Washington of the Century Foundation explained in her article “Diversity in Schools Must Include Curriculum,” that “the importance of diverse history curricula is far from abstract. To teach history accurately, one must teach about the variety of ethnicities and cultures which make up our world. Eurocentrism is harmful first and foremost because it [is] false. However, diversity in curricula is about more than just teaching a full view of history; it is proven to empower students of color.” Eurocentrism is the tendency to express things “in terms of European or Anglo-American values and experiences,” according to Merriam Webster Dictionary.

For example, in a study conducted by members of the Stanford Graduate School of Education, ethnic study classes were implemented in high schools located in San Francisco to test if benefits could be observed among high school students. The researchers found that students who took the ethnic studies class had increased grade averages, attendance and number of courses completed for graduation. While this study tested a specific curriculum focused on “the roles of race, nationality and culture on identity and experience,” BVH should aim for similar results with a wider variety of history classes.

Some may argue that it is more important to learn general history than taking history classes dedicated to specific groups. However, bringing these new options to BVH would not cause any students to learn less history from their required courses, precisely because those courses would still be required by California’s educational standards and BVH graduation requirements. For example, the content in a U.S. History will not be in any way compromised by having a separate, additional LGBTQ+ History class, and would rather only be enhanced for that

History classes focusing on historically underrepresented groups would allow students who want to approach history from another angle to delve into an informative class, viewing the past through a different lens. Historically underrepresented groups are often equally underrepresented in typical high school history classes, and bringing a new variety of history classes to BVH would work towards remedying this issue.

Especially since 90.7 percent of BVH students are people of color, according to the California Department of Education’s DataQuest report, classes that specifically teach the impact other ethnicities have had on the U.S. would be especially relevant on campus. Students should have the opportunity to learn the history that they identify with. In contrast, educational material has been found to still offer a Euro-American focused view in current U.S. History courses.

“While content related to African-Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans has been added, deeper patterns and narratives that reflect Euro-American experiences and worldviews, and that have traditionally structured K–12 textbooks—particularly history and social studies texts—remain intact,” Christine Steeler wrote in her research review published by the National Education Association titled “The Academic and Social Value of Ethnic Studies.”

Locally, the San Diego Unified School District recently approved the addition of an ethnic studies requirement for upcoming school years. Throughout the nation, other high schools and universities are doing the same. Exposing students to in-depth representations of diverse history may lead students to find a passion they will pursue in higher education, and possibly throughout their career. History has always been a multifaceted story, and the classes offered at BVH should represent that to truly educate students who graduate from the school.

All history classes have value, but time is limited. Teachers are even more restricted to cover certain topics in World History and U.S. History when there is an AP or IB test at the end of the school year. If BVH were to offer semester-long courses that focused on LGBTQ+ history, Mexican-American history or Jewish history, to name a few, then students would be broadening their understanding of the world’s history without any caveats. Moreover, semester classes can be paired based on student interest to create a year-long elective of diverse history.

BVH students need other teachers to follow the lead of DeVore and propose more diverse history classes until students have the opportunity to learn histories they can identify with and learn from, in addition to the current history classes they take. We live in a dimensional world, one that has been experienced through many eyes; the narrative of our history should be a story told by all voices.

I am a senior at Bonita Vista High and a fourth year staff member on the Crusader. I am now co-Editor in Chief, and previously was News Editor, Features...

I am a senior at Bonita Vista High and a third year staff member on the Crusader. This year, I am co-Editor-in-Chief, and previously was Opinion Editor...