BVH students attend their Automotive Technology class.

Together but unequal

Analyzing the disparities in the educational experiences of BVH students

In every school he has taught at, Advanced Placement (AP) United States History teacher Don Dumas has consistently seen that Hispanic/Latinx and African American students are less likely to take advanced classes than Asian and White students. This is also the case at Bonita Vista High (BVH).

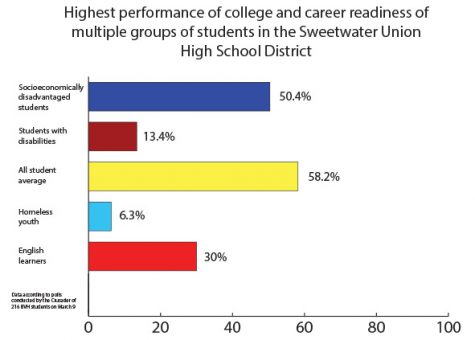

On average, Hispanic/Latinx and African American students were least likely to have at least 1 AP or International Baccalaureate (IB) class according to a poll conducted by the Crusader of 216 BVH students on March 9. The disparities between ethnic groups on campus continue when researching student support by staff, pursuing higher level education and more. Beyond that, socioeconomically disadvantaged, foster, homeless and students with disabilities perform worse on average academically throughout the Sweetwater Union High School District (SUHSD) than the student average.

Looking into the causes

Students from a variety of ethnic, societal and economic backgrounds coexist on BVH’s campus, however these groups consistently show different levels of academic performance, college preparation and experience. These differences can—and have—impacted their educational experiences, including the rate of failed classes, as well as a decrease in enrollment to advanced courses among certain student groups.

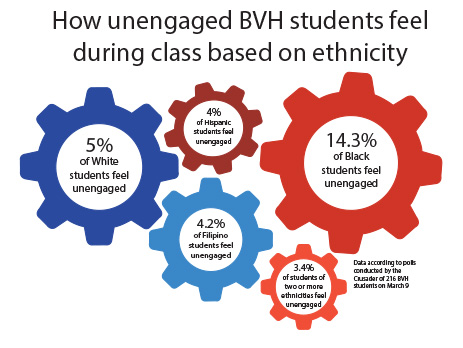

Data collected by the Crusader reflects many differences in educational and classroom environments, such as level of student engagement, how much students feel expected to attend college, which students are more likely to be failing courses and which students are most likely to be passing AP tests. Causes for these trends can be found at the district level, where administration can examine the common trends following demographics and their impacts on the district as a whole.

“Across the district, Asian and Filipino students tend to perform higher than Hispanic [students] and in some cases African Americans perform lower, on average. Because of this we want every school to really think deeply about the things that impact student performance,” SUHSD Director of Research, Evaluation and Accountability Daniel Winters, Ed.D. said.

District evaluations conducted by Winters’ department reveals that a many factors are directly influencing the performance of certain student demographics. Each school year, the district focuses on addressing disparities between a couple student demographics.

“Obviously there’s curriculum and instruction, teacher quality, school culture [and] family support, so it’s really a complex set of factors that all contribute to our student performance,” Winters said.

Propositions to fix these issues come in the form of district composed implementation plans. These plans follow different steps to meet the unique needs of the student’s demographic with the goal of closing minority/majority disparities. However, they are organized by different people who could improve in communication, which is something Winters expressed concern for.

“We feel like there are some gaps in communication between different teams [that work with students with disabilities]. We need to see [that there is] more co-teaching for these students who are struggling, where we see those teachers work together,” Winters said.

While the district attempts to fix gaps between disadvantaged student groups such as those with disabilities, certain groups do receive less attention than others. According to Winters, one such group is the male gender, which statistics have shown to be underperforming compared to their female counterparts.

“It’s kind of a pet peeve of mine, because the data for the last 30 years has shown that girls outperform boys significantly. In every point. I think that’s a trend we should give more attention to because boys definitely are not doing nearly as well,” Winters said.

Although the differences amongst student demographics are a problem facing the district at large, they begin with the classroom and the type of learning environment students are surrounded by. This is especially true when social biases, such as racist bias, are present in the classroom.

“Bias plays a role there somewhere,” Winters said. “I have no doubt that it plays a role in student performance. We have to work on that within the district, in terms of helping to overcome those [challenges].”

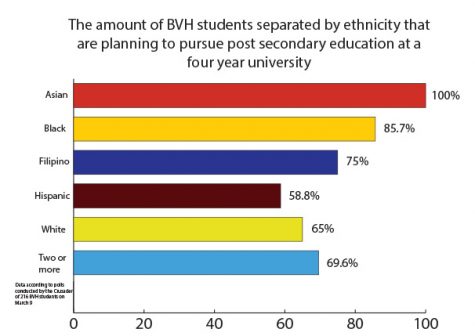

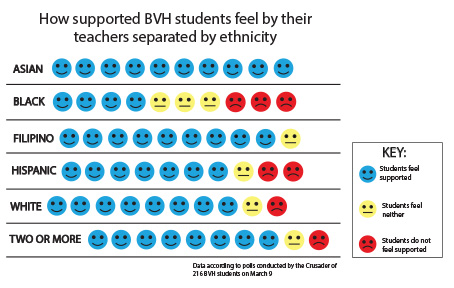

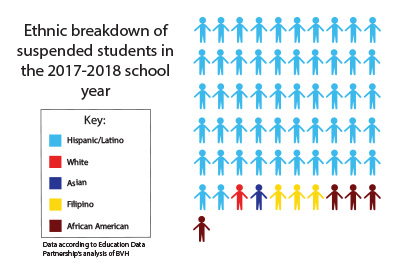

According to Winters, if teachers or administrative figures favor a certain student demographic, it influences the learning experience of all students within the classroom. Statistics gathered by the Crusader display a trend amongst African American and Hispanic/Latinx students who feel as though they are not supported by their teachers or administration, and thus are less likely to pursue secondary education at a four year university or community college. African American students are also less likely to feel engaged in their classes.

“I cannot answer for the kids at BVH and why they answered the question in the way that they did. But generally speaking, the K-12 content in US schools, and [how] teachers deliver it, are racist and exclusionary toward Black Americans. In addition, many teachers are racist at worst, and practice implicit bias against their Black students at best,” Dumas said.

This mindset is reflected by student performance in standardized testing, as well as participation levels in tests for college admissions. Filipino and White students are more likely to take the American College Test (ACT) or the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) than Hispanic/Latinx students.

“It’s been a challenge. The district is always trying to be transparent with all levels of academic success. We will continue to monitor the standardized testing platform and all information that is shown,” Board of Trustees member for District Two, the geographic region that includes BVH, Kevin Pike said.

In the classroom, every student should be given an equal and appropriate level of support they need to succeed, according to Dumas, who has taught both regular and advanced classes. However the variety of factors that come into play provide a substantial challenge.

“School should be about learning, but somewhere along the way we have converted our schools to be factories of compliance, obedience and conforming. And when a student doesn’t do those things, school becomes very punitive,” Dumas said.

Factors influencing students outside of the classroom have also been taken into account by administration, such as a student’s financial situation which has a significant effect on student performance according to studies done by Winters’ department.

“We tend to see, not unlike the rest of the schools in the country, that economics tends to make the biggest difference,” Winters said. “Students at schools at higher economic areas tend to perform better on average, but we do see some outliers of schools in our district that I would say are worth noting.”

Although financial aspects are strong influences, the impact is dependent on the school’s standards in academic performance. According to Winters, evidence of this can be found in BVH’s own performance, as students who are low income are performing better at BVH compared to the same level income students in schools to the west side of Chula Vista, where there are overall lower socioeconomic levels among students.

“One interesting data point that I’ve seen is that students who are low income are doing better when at a school that has overall higher scores. […] One aspect of student performance is climate and culture. It’s about the expectations of that school,” Winters said.

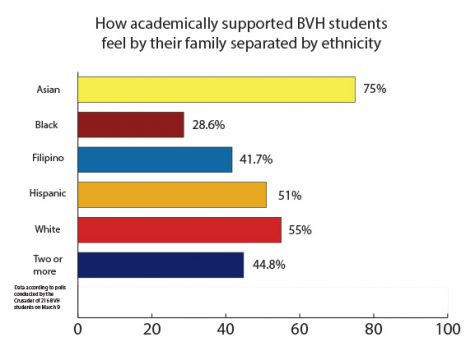

Financial problems are categorized as issues occuring within a household, suggesting that matters outside of school can also be the source of influence when it comes to student demographic difficulties. African American students are the most likely to feel unsupported by their family in their academic pursuits; students of that same ethnic group also are the least likely to enroll in AP or International Baccalaureate (IB) courses.

“So much of how things [success rates] end up are less about who has potential and more about who understands the bureaucracy; what researchers call social capital,” BVH Principal Roman Del Rosario, Ed.D. said. “I realized it’s not about the students’ potential. Certain students have parents or others that are really an advocate for their child. I didn’t have that and most of my Latinx friends didn’t have that. So most of us ended up in regular courses instead of accelerated. It starts early, and it helps having parents with that social capital and to know to talk to your counselors.”

Situations involving a student’s household environment are factors out of reach to school staff and administration. However, Del Rosario believes that it is possible to improve a student’s social capital by working with parents and staff alike.

“I really think that a lot of those factors are out of my realm of influence, but many are within my realm of influence,” Del Rosario said. “I think I can engage parents to be partners to get their children to work harder and take more rigorous classes.”

Ultimately, the root of the conflict dealing with the differences among student demographics comes from a number of factors. However, the impact has varying effects depending on a student’s environment at home and on campus. Different families focus on different things with their children, giving students support in different ways or at different levels. Nevertheless, Del Rosario is committed to giving all student demographics the same standard of education.

“When I was a teacher, my parents used to ask if the children behaved. I thought the real questions should be, ‘Are they learning?’ ‘What are they learning?’ ‘What do they struggle with?’ ‘What are they having trouble understanding?’ But that’s why I really think it’s essential that we have partnerships early on and we get students on the right track from day one,” Del Rosario said.

Looking forward to solutions

The differences among the experiences of BVH students become apparent when reviewing data, and these experiences are influenced by different factors at different levels within the SUHSD, BVH and individual classrooms. It is in those same areas that solutions and plans can be implemented to improve the weaknesses identified through research and data.

SUHSD has a Research, Evaluation, and Accountability (REA) department led by Winters in order to eventually “enhance student and staff learning and overall flourishing.”

“[The REA department is] constantly looking to make sure that we can provide data in such a way that the strengths, weaknesses and gaps are apparent, because we wanna deal with those gaps. We wanna close them. Highlight strengths and build on them, but we wanna look at our weaknesses too,” Winters said.

Part of the work the REA department does is to help each school within SUHSD to create a Flight Plan for Student Achievement (FPSA) based on the data they find for one academic year. The goal of this flight plan is to improve student achievement.

“Every spring, we do what’s called a flight plan for school improvement, the Flight Plan for Student Achievement. Every school does it yearly and it has to get approved by the Board of Education. Then they implement it throughout the year, and in spring we analyze their progress. We do that for every school, and even district-wise,” Winters said.

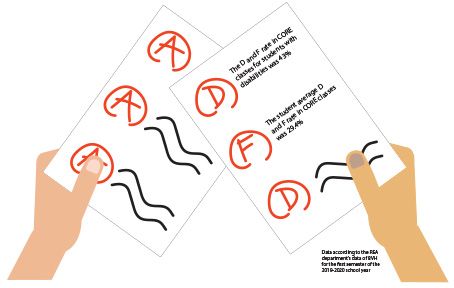

Furthermore, every year the district focuses on certain weaknesses based on input from a variety of staff members throughout the SUHSD. For the 2019-2020 school year, one student group that was chosen by staff were students with disabilities. The REA department works with each focus student group in different ways to improve their performance level when they are under performing.

“Students with disabilities for example, are academically doing extremely low in regards to math. We focused on math initially. We look at things like student achievement and often it’s really critical what course a student takes. We did some analysis on student’s placement in their classes based on their [Individualized Education Program] IEP. […] Plus [we look at] the types of instructional support [we implemented] more co-teaching for those in special ed, where special ed teachers work together,” Winters said.

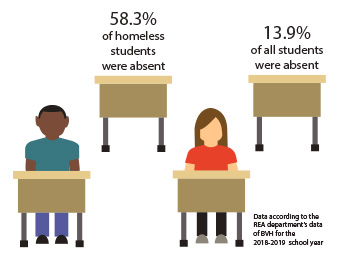

The other two student groups being focused on this school year are homeless students and those in foster care. Winters and his department have identified different weak areas within these groups, and have been working on different solutions.

“With foster and homeless students the situation is very different. They both have very high chronic absence rates and we have a system of support that can help them. A lot of that is one on one connecting with kids, having people checking in on them and being with them when they need it most. Each group has a different focus depending on which areas they’re struggling in,” Winters said.

Winters stated that through the plans implemented this school year SUHSD saw “satisfying” improvements. However, he acknowledged that in the future more work will still need to be done for these groups, and students with disabilities particularly need more efforts dedicated to.

“We feel like we now have a good process in place to allow for consistent analysis of school performance and therefore better improvement plans. We developed a process that is very specific about how to do a needs assessment, a root-cause [analysis] and develop a plan based on that root-cause. Those steps we are now incorporating into every school in the district’s site plan development,” Winters said.

The work of Winters’ department is one way that the data and student achievement rates of BVH students are changed over time. This is the main purpose of the REA department, which Winters stated focuses on equity for all students.

“If [our work] doesn’t ultimately help the students then we’re not doing our job. Our job is to help teachers, leaders and counselors get the information they need to make a better decision for that student the next day,” Winters said.

While the REA department helps create structure methods for improving student achievement, each individual school has their own solution implementation depending on student performance.

“[Solution plans] depend on each school and it would be the job of each school to dig deep into their own performance to find the reasons for poor performance or good performance depending on how you look at it,” Winters said.

Del Rosario believes that in order to raise certain areas of student performance, BVH has to convey high expectations to students and support them in order to reach that expectation.

“We have to raise the expectations for students, we have to partner with parents [and with the] community. The question isn’t ‘students are failing? Let’s make things easier,’ the real challenge is let’s keep expectations high but provide more support, more ramps for students to get there. Whether it’s co-teach for students with special needs, [Sheltered English Immersion] (SEI) for English learners, after school Saturday interventions to give extra time and the Friday [Professional Learning Community] PLC times so teachers can really collaborate and share best practices—it’s all part of that puzzle,” Del Rosario said.

Del Rosario witnessed the same trends in academic performance among ethnic groups that exist at BVH today when he was a student at Hilltop High. He recalled being one of the only two Hispanic/Latinx students in his advanced class when about half of the entire student body was Hispanic/Latinx.

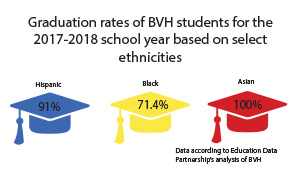

According to polls conducted by the Crusader, 47 percent of Hispanic/Latinx students reported that the majority of the classes they were currently taking were regular, while 42.9 percent of African American students, 35 percent of White students and 16.7 percent of Filipino students reported the same. Del Rosario believes that student achievements can be improved—however, they need to have guidance in their life.

Sophomore students complete classwork in English and Drama teacher Rosamaria Sias’ English 10 Accelerated class.

“Things don’t change overnight, but I think everyone deserves a champion, and I think some students—I’ve seen it with my own students when I was a teacher in LA, I see it everyday at Bonita Vista High—where there’s often a case where there’s an adult who [is] a champion for a student, and believes in that student more than that student does in themselves and you just have to keep believing in students,” Del Rosario said.

Dumas agreed stating that, “students need people in positions of influence to advocate for them and help create opportunities for their success.” Dumas also furthers that by having more African American teachers, African American students may feel more generally supported by their teachers. At BVH, while 80 percent of White students felt generally supported by their teachers, 69 percent of Hispanic/Latinx students felt generally supported by their teachers and 42.9 percent of African American students felt supported by their teachers. Students should not all get the same level of support, but rather each receive the amount of support they need, Dumas believes.

“Every student should have the appropriate level of support that they need to succeed. Different students have different needs at different times. There isn’t an easy, one-time, fix all cure for student support at all times. So this is a moving target, you see? I don’t know how to accomplish this, but I know we should never stop working toward it,” Dumas said.

In individual classrooms, connections can be made between students and their teachers that help them feel motivated, supported and expected to go to college. However, currently at BVH 20 percent of Hispanic/Latinx students stated they did not feel generally supported by their teachers, 28.6 percent of African American students do not feel generally supported by their teachers, 10 percent of White students do not feel generally supported by their teachers and zero percent of Asian and Filipino students do not feel generally supported by their teachers.

“Teachers are just one part of the team to improve the statistics. It takes many individuals all working together to change and help students in their success,” Pike said.

According to data provided by the REA department, the D and F rate for socioeconomically disadvantaged students at BVH was 7.1 percent higher than the student average in CORE classes during the first semester of this school year. Dumas does believe, however, that teachers can help to close this gap by “taking an interest” in struggling students.

“Too often we [teachers] take a ‘sink or swim’ mentality. We give out work and grade work and give out work and grade work and on and on. If a kid isn’t keeping up, our solution is to give him more. Well, doing more of something that isn’t working doesn’t help anyone,” Dumas said. “We need to change what we teach and the way we teach so that our curriculum reaches and speaks to these marginalized groups. That doesn’t threaten the position of the dominant group. Because good pedagogy is good for everyone. But we can’t ignore this problem and think that it is going to miraculously fix itself.”