My name is Kara Barragan and this is my fourth and final year with the Crusader. As a freshman I was on the lookout for an outlet where I could put out...

November 29, 2020

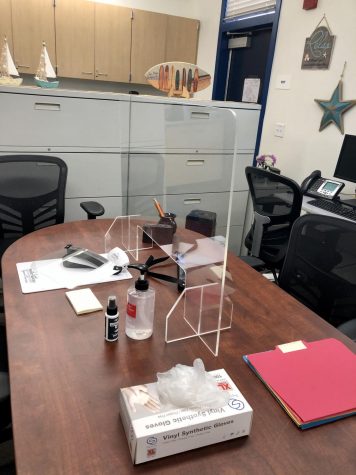

BVH psychologist Martha Ingham, Ed.D., sits in her office at BVH. Ingham frequents BVH 5 days a week to finish her work.

With the COVID-19 pandemic stretching out for months on end, incidents like scraped knees from tripping on the track and bad headaches in need of Advil are no longer a worry for Bonita Vista High (BVH) Nurse Paola Garcia, Registered Nurse (RN). And with students quarantined at home, BVH Psychologist Martha Ingham, Ed.D., no longer sees the faces of students who walk in her office, rather now it stands more isolated than ever.

Garcia and Ingham’s worries are much more than the day-to-day occurrences that took place before March 13, the day in which all San Diego County schools were shut down. Due to this, the two have adapted by creating new daily routines with their work which is distributed on and off campus to aid students and BVH staff.

Garcia is one of the first to step foot on campus at 7:30 a.m. The first item on her agenda is to conduct mandatory temperature checks on staff members who enter the campus. By around noon, Garcia finishes with the majority of temperature checks for the day. These workdays are “a lot quieter and less hectic” than before the pandemic, according to Garcia, but she remarks how much she misses working with students in person.

“[What motivates me throughout the day is] looking forward to the end of the pandemic where kids can safely go to school and we can do what we love which [is] help students grow into amazing young adults,” Garcia said.

Garcia utilizes the rest of her time at BVH concentrating on other projects such as relocating and cleaning her office, working on immunization compliance, creating digital files, attending staff and parent meetings or conferences and getting ahead on paperwork. In terms of immunization compliance, Garcia makes sure that students are up to date on their immunizations by contacting parents if their child is missing shots and referring them to a clinic.

“Pre-pandemic, my day was predominantly occupied working directly with students either through providing first aid or scheduled treatments. I didn’t even own a chair pre-pandemic,” Garcia said. “Now I am using this time to clean out files, relocate and organize my office, plan and coordinate for re-entry.”

Before BVH’s closure, Garcia sent notices that were needed to give to parents by printing them out for students to take home. Now, all of these consent slips, doctor orders and health updates are converted online by Garcia since she is not able to send these forms home with students. She then uploads them on BVH’s school website.

Additionally, Garcia has been a part of a reopening committee working on BVH’s plan to make a safe return to in-person learning in order to lessen the potential danger to students. She believes when BVH will return to in-person learning, her workday will mainly consist of providing direct student care with assessments, screenings, treatment and counseling.

“[With this reopening committee] I can contribute to how we should re-open, what safety measures to take [and] what purchases are needed to provide the safest environment. When students come back to my office, it most likely will be moved to better accommodate students who may show symptoms of COVID,” Garcia said.

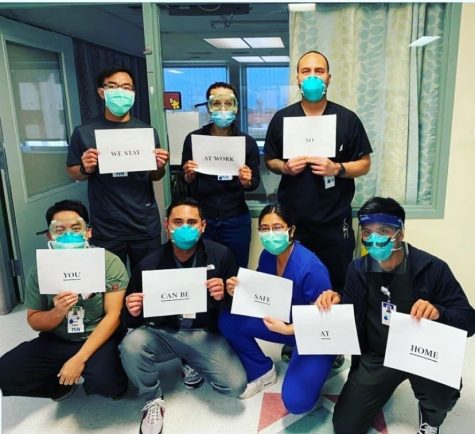

Outside of her office, Garcia has dealt first-hand with the global effects of COVID-19 working as an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) nurse. Garcia has been an ICU nurse for 10 years. She adds that her profession works at a hasty pace, being both physically and mentally demanding and requiring “critical thinking, split judgment and flexibility,” which have given her ideas for future plans with BVH’s reopening. With the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recommendations at the beginning of quarantine, she took these recommendations “extremely seriously” and did not visit her family and friends for months while working as a first-line responder and a school nurse.

“At the beginning [of the COVID-19 crisis], [the hospital] didn’t have enough personal protective equipment. We didn’t have the ability to know if a patient was positive until several days later. We didn’t understand how the virus affected the body, what the best treatments were or how easily as health care workers we could contract it from our patients. Many nurses quit or retired early, [this] caused an additional strain on those of us who stayed,” Garcia said.

For Ingham, aiding students who are struggling with distance learning has become a critical task, as many have found themselves isolated and distraught. To help students, Ingham has been working with a team of Special Education teachers to fulfill deadlines for student Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings.

“[My] successes [with work so far] are that we’ve been able to meet our deadlines for student IEP meetings. Our team of Special Education teachers and providers for students with IEPs have been exceptionally hard at work to support [as] best as possible given the circumstances,” Ingham said.

These student IEP meetings are required to take place once a year, functioning as an outlet to overlook baseline data on what a student is capable of doing academically. The goals in these meetings are to address areas of necessity and are expounded in a way to be measured; soon after, the goals are reviewed at the end of each semester and at the annual IEP meeting.

In addition to these daily duties, Ingham has contributed in conducting psychological testing such as IQ and cognitive processing for Special Education purposes. Moreover, she has been supervising instructional and health care aides, as well as working in student study teams and administrative meetings with BVH Principal Roman Del Rosario, Ed.D., and serving as a member of the crisis response team on campus.

“We have a very large program for students with special needs,” Del Rosario said.“[Ingham] was in meetings with teachers, instructional assistants, healthcare assistants, parents, social workers and advocates and now she does a lot of that work, but she does have [very different work] than before [the pandemic].”

In the case that a parent, teacher or IEP case manager, usually a Special Education teacher or another member of an IEP team, does not bring up the students’ struggles to Ingham’s attention, they show up on students’ progress reports. To resolve this issue, Ingham downloads a spreadsheet of students with D’s and F’s and seeks out teachers’ input on the reason regarding their low grades and asks for tips on how students can improve.

The IEP case manager then develops an “action plan” with the student when a student’s grades do not improve. From there, the IEP case manager contacts their parents, resulting in an additional IEP meeting to “problem solve,” according to Ingham.

In order to make sure students are staying on track with school work, Ingham has been forming partnerships between students, teachers and parents over video calls. Ingham speaks with parents and encourages them to view their child’s assignments on Jupiter Ed and Google Classroom to eliminate confusion.

Del Rosario has expressed how both Ingham and Garcia have exceeded his expectations when working through a time like now. He believes the two and many other staff members will work to make the school resume transition smooth and that the two are “ahead of the curve” in the process of returning back.

“All of us went into education because we enjoy working with students. It’s hard to get a sense of our impact from a distance,” Ingham said. “However, from my training as a clinical psychologist, I have skills that help me get a sense of people and concerns by being physically present with them; that is, it’s not so much what a person says, but how they say it and how they posture themselves, and there’s that gut instinct as well that I use to help me understand what is happening.”

My name is Kara Barragan and this is my fourth and final year with the Crusader. As a freshman I was on the lookout for an outlet where I could put out...