“But where are you really from?”

BVH students speak out about experiences with microaggressions

According to Oxford Languages, a microaggression is a statement or action that indirectly discriminates against members of a marginalized group, such as a racial or ethnic minority. Three students from Bonita Vista High (BVH) have shared their experiences facing this subgroup of racism with the Crusader.

Black Student Union (BSU) Co-President and senior Renee Fagan shared conversations about the microaggressions she encountered while conversing with her friends when she was younger. In one instance, she was in summer camp and she flat ironed her hair. When everybody saw her hair, they were complimenting her “because [her] hair looked straight and it looked like theirs,” according to Fagan.

Another time, a close friend of Fagan commented, “You know what, I don’t really see you as Black; you are just one of us.” Years down the line, Fagan realized that these were not compliments; they were from people who thought she didn’t look “Black enough” or “act Black enough.”

“I’m always used to being the only Black kid. [Summer camp] was a place where I was just, once again, the only Black kid. I didn’t notice it before, but some of the things that were said to me did stick with me years later. It’s not overt racism, like being called slurs, but those small microaggressions remind me that I’ll never be fully appreciated as a Black woman in this country,” Fagan said.

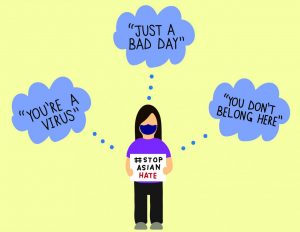

Junior Olivia Martinez expressed that the majority of the racism she has experienced consisted of microaggressions. She feels that racism starts as microaggressions and then transforms into “something really big.” As an Asian American, Martinez has been asked, “Where do you come from? What are you?” When she answers that she is from America, the answer is often, “No, where are you really from?”

“[Comments targeted at my appearance make] it hard to feel American because my facial features or my body type is not the Eurocentric standard that we know of, especially here in America. I feel like most people who think of America think of the white America. Being Asian, we aren’t really treated as American. It’s those microaggressions that make one feel they don’t belong here,” Martinez said.

In her sophomore year, junior Mia Gonzalez was having a conversation with her friend after class and was caught by surprise when her friend made an insensitive comment. He jokingly said, “my [Gonzalez’s] kind [Latinos] are drug dealers and rapists.” Gonzalez did not know how to react and laughed it off to avoid causing a scene. However, deep down it hurt because she thought he was a friend that respected her culture and race.

“A lot of young kids who are growing up are now hearing the news and growing up thinking certain things about one group of people because of what they’ve heard from their parents or from the television. They don’t have the freedom to make that choice on their own. I think the past two years, we really saw how these stereotypes flooded the internet and politics. There [are] things you don’t realize until [they] become big,” Gonzalez said.

Through her experiences with microaggressions, Fagan has learned to be more outspoken and stand up for what she sees as right. When a teacher or a peer mentions something that goes against her morals, she says she sticks up for herself and the community she is a part of. Looking back, Fagan felt she could have reacted differently to the microaggressions she faced.

“At the moment, it’s embarrassing because you’re getting yelled at in front of people, getting ridiculed for the way you look or the way you act. Looking back on it, I now sit in a position of knowledge and less ignorance. I am just mad at myself, honestly questioning, ‘Why didn’t I say something? Why don’t I speak up,” Fagan said.

According to Martinez, microaggressions are harmful to students who are still discovering who they are. She said when phrases that make them feel they don’t belong are verbalized to them, they will feel like they don’t belong. Martinez grew up with an Asian and Latino background. As a mixed child, she felt that she wasn’t accepted in her own community. Her peers would tell her, “you’re not enough [Asian or Latino], or you’re too much of it.” To Martinez, all she heard was, “you don’t belong here.”

“It causes a disruption in one’s identity because there is this whole idea in America [that] everybody is equal, everybody’s treated the same. When you aren’t treated like you belong somewhere, somewhere you’re supposed to call home, it’s really harmful and just creates a rift in the community that you’re in,” Martinez said.

Gonzalez noted that she has concerns with using outdated history textbooks, and expressed that inaccurate information about minority groups could hurt student’s academic development. Gonzalez believes history books shouldn’t be choosing what they want to tell students; rather, they should inform them about all historical events so students are more educated about social topics like racism and microaggressions.

“We learn history to not make the same mistakes as the past. I have a friend who tells me a lot of historical facts that schools don’t talk about, and it changes your perspective because history is a lot about perspective. In order for students to grow and make a good call on a certain event, we should be able to know everything that happened before,” Gonzalez said.

Martinez said she values having resources to educate herself about current social issues. She wants to further her knowledge about different cultures and hopes that others do too. She believes this will help foster the idea that everybody is different and deserving of respect no matter their background.

“[We have] to raise the voices of those who are constantly experiencing racism: the Black community, the Hispanic [and/or] Latino community, the Asian community and the Indigenous community. Those are the voices we really need to raise right now. Looking back at history, we have all faced oppression. We have faced all the hatred and mistreatment,” Martinez said.

In recent months, Martinez noticed that some people are uncomfortable talking about racism. She believes this is either because they don’t think racism is their problem or because they are involved in it. However, she stressed that racism and microaggressions happen on a daily basis, and “no matter if you’re Black, White, Asian, it’s a human problem,” so everyone has to work together to combat it.

Fagan believes there is a step before people come together to fight against racism: caring. She realizes that some students and adults are indifferent about racial injustice, and hopes people start realizing that racism will not just disappear if they avoid discussing it.

“That’s the scariest thing. People don’t care because it’s not them. So for the future, I want to see more people caring and more people using their resources, using their voices, even if it doesn’t seem like a big thing,” Fagan said. “I hope more people realize what’s been happening, that the racism in this country is an epidemic that is plaguing millions of lives since day one and hopefully they want to be a part of the change.”

I am a junior at Bonita Vista High, and a second year staff member on the Crusader. I love being able to meet new people, and having conversations with...

Wish OSK113 • May 20, 2021 at 9:00 pm

Very good article.

Jared Phelps • May 15, 2021 at 6:31 am

I’m glad your article is doing just what Olivia said “raising the voices of those who are constantly experiencing racism.” Thank you for taking the time and using this platform to make their voices and experiences heard.