The Fab Four

On a chilly Friday afternoon, four teachers sat together in animated discussion. Teachers Michelle Mardahl, Ph.D., Jennifer Ekstein, Joseph Szakovits and Priscilla Soto met that day, just as they had countless times before: some having done so for almost twenty years and the newest member for only two. Today they came together as the Biology Accelerated Professional Learning Committee, or PLC, with the shared goal of perfecting the daily lesson plan for their freshmen students. Strangely enough, none of them originally thought they would become teachers.

The senior member of the group was Mardahl. A teacher since 2003, she wore a boldly rainbowed, tie-dyed t-shirt with the title “Sloth Club” plastered on the front. She was the advisor of this club at BVH which fundraises to save endangered animals around the world.

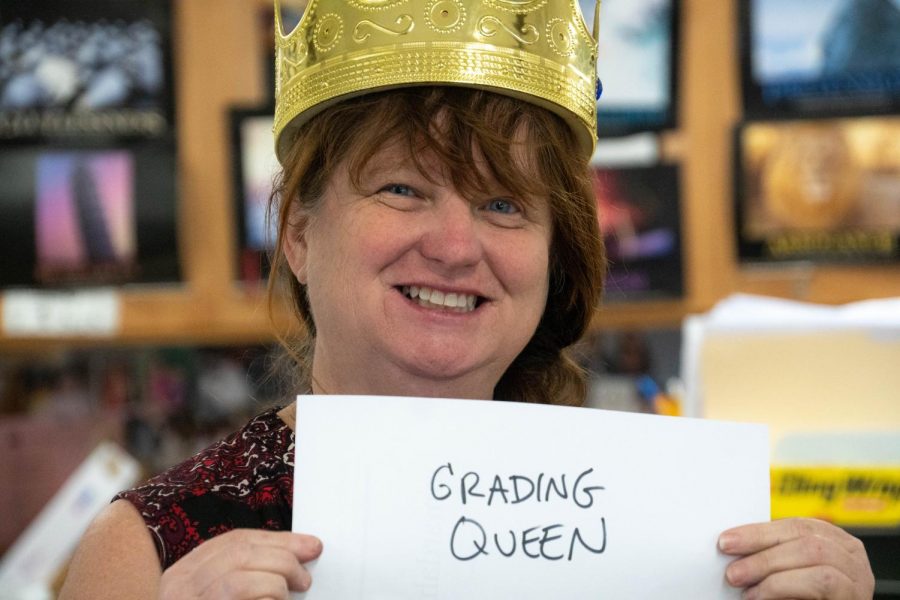

Earlier that day she had worn a plastic golden crown, exclaiming to her fifth period class, “I’m the grading queen!” slapping a massive pile of freshman homework packets onto her desk. But this self-proclaimed title was not one that Mardahl would have expected to hold when she herself was a student. Since the time that she was a sophomore in high school, Mardahl was convinced that she wanted to be a scientific researcher, dedicating her life to the laboratory.

But, as is the case for so many, life got in the way. Her daughter, Pascal, was in the first grade while she was away from home, teaching a class from 7:00 to 10:00 pm on Monday nights. She was doing research full time and teaching at night, and it reached a point where something needed to give. “Research is not a nine to five job. You’d have to be willing to move and there’s a lot of sacrifice. And I chose family over that,” she said plainly.

Abandoning her childhood dream of becoming a researcher, Mardahl set her sights on becoming an educator. She was looking for a personal connection with students, and was not fulfilled when working with the glassy-eyed community college students who attend night classes only when they feel like it. She felt isolated as a Biology teacher at Southwestern College and so, she made the choice over fifteen years ago to begin teaching at Bonita Vista High.

“One thing frustrating about college is that you saw people come in, they would take one test, they fail and disappear. You couldn’t really work on them. But you can in high school,” Mardahl said compassionately. She sounded sincere. She paused, collecting her thoughts and continued. “You can get somebody to go from writing a really crappy lab report to a good one. You can work with somebody who doesn’t have a work ethic and try to get them to be better.”

Mardahl’s line of thought was interrupted by Ekstein, who had just floated into her classroom through the “Tunnel of Love,” Ekstein’s nickname for the hallway that connected their two rooms. She began searching for handouts for her Biology Accelerated students that were stuffed in massive piles of paper in the front of the classroom.

Ekstein was small in stature, only 4’11. But for what she lacked in size, she made up for with her larger-than-life personality. With curly red hair, she seemed to be the reincarnation of Ms. Frizzle from the Magic School Bus. Today, she wore a leaf-shaped fanny pack, bright leggings and a t-shirt.

Ekstein’s path to becoming a teacher was certainly an unconventional one. She went into college determined not to become an educator, as this had been the occupation of both of her parents. She wanted to become a vet. She loved animals: as a kid she’d had guinea pigs, rabbits, tortoises and everything in between.

Sometimes life has a way of handing you exactly what you need. And that’s what happened with Ekstein. To pay for textbooks in college, she began tutoring AVID for science. “I fell in love with it,” she said, speaking with a fondness and nostalgia that only those who share the vocation of teaching could fully comprehend. “And instead of becoming a veterinarian, I went into the credentialing program at San Diego State and I ended up becoming a teacher.”

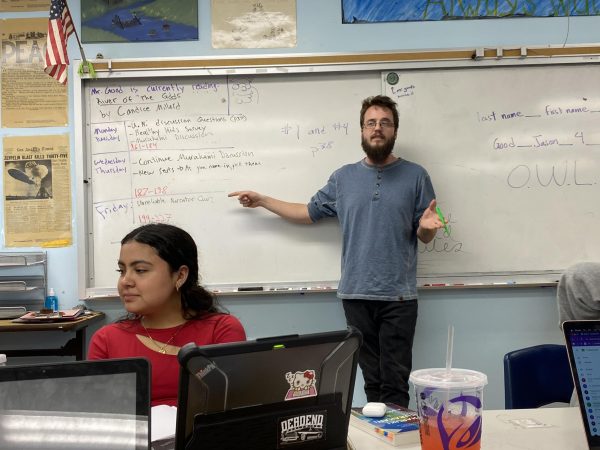

The third most senior member of the Bio Accelerated PLC was Szakovits. Known by his students to pace around the front of his classroom, for his erudite teasing and bone-dry humor, he now sat still in a small student desk. Wearing a button-up white shirt and khakis, he was positioned rigid-backed and attentive.

Szakovits was just finishing up his seventh year teaching at BVH. Before that, he was a student teacher. “If you count those [years as a student teacher], which some people do, some people don’t, it’s my ninth year. Oh God!” he said in an exaggerated, dramatic tone, eyes widening with feigned horror. He spoke as if he had been teaching for fifty years, when he actually was one of the younger teachers on campus. But beneath his humor was a twinge of nostalgia towards his years as a educator.

This reality is one that would have been shocking to Szakovits when he first arrived on the UCLA campus fifteen years ago. A wide-eyed freshman, teaching was absolutely not on the radar. He didn’t have the right personality. He was emotionally isolated and lived in his head—not exactly the teacher-type.

By 2009 his plans to become a researcher had gone awry, but it wasn’t for any of the usual reasons. In UCSD’s Biology Ph.D. program, Szakovits didn’t have bad grades, in fact, quite the opposite. It wasn’t that he had lost interest in the subject. He’d loved biology as far back as he had memory, collecting books about animals and dinosaurs as a kid. But one day in mid-2009, Szakovits came to a realization. “I really, really hated working in the lab. And I realized that the only thing that I actually liked about it was getting up and explaining things in front of people. So it was a natural next step to do this instead.”

Why Szakovits hated working in the lab is an even more difficult question to answer. To curious, eager freshmen students who ask him why he became a teacher, he tells the story of having to kill a mouse in a lab experiment. The story isn’t pretty. “They asked me to kill a mouse and I still remember what it felt like when its neck broke. And I still remember,” he recalled, eyebrows furled as if troubled by the recollection. “I remember kind of being okay while I was doing it. But then after that I couldn’t sleep for days.”

For Szakovits, this was one of the last straws. But what pushed him to leave was a situation much more disturbing. Two of his colleagues in the graduate program committed suicide in a period of less than five weeks. “I was never 100 percent clear what the first one’s reasons were. But the second one was definitely related to the stress associated with the program itself,” he explained, his voice getting quieter and slower as he brought back these memories, as if he were re-living the experience. “I don’t want to bash anybody, but [UCLA administration] didn’t really seem interested in making any changes after that happened. So that was like, okay, I definitely need to get out of here.”

And so, Szakovits dropped out of the Ph.D. program at UCSD in 2009. Convinced that he wouldn’t become a researcher, Szakovits decided to pursue biology as a educator. In the teaching program at SDSU, Szakovits did a year of observation of teachers in action. Coincidently, these teachers were Mardahl and Ekstein. Soon after, he would begin teaching along these two “mentors” in 2012.

When asked why he enjoyed teaching, Szakovits answered without a moment’s hesitation. “The students. That’s a real easy answer. I mean I do love the material, but what really makes it special is I get to meet 150 new different people, every single year. They all have different backgrounds, different attitudes, different personalities, different senses of humor. It took me a while to fully understand just how enriching that was, but it really, really is.”

The newest member to the group, Priscilla Soto, came to Bonita Vista High in 2017, where she resides in room 808. She wore a knit sweater and large, hoop-like earrings designed to look like they were carved out of marble. Her hair was tied up in a high ponytail, the roots a dark brown which faded into emerald green locks.

Only years before, Soto was convinced she wanted to become an optometrist. At SDSU, she would attend medical conferences and shadow professional optometrists: her dream profession since high school. However, there came a point that Soto determined that she “just couldn’t hold that passion for it anymore.” Having worked at the YMCA with younger kids, she realized that she loved working with students and decided to give teaching a shot. “I was like, ‘What do I do?’ After telling people that you’re going to be a doctor for so many years, switching is kind of an odd thing to do,” Soto began. “I realized [teaching] is what I want to do. I love this. I loved going to work, I loved going to school. I was like, ‘I can put them both together. How cool is that?’”

Given how new she is to the teaching scene, Soto admits she’s still figuring out her teaching style. However, she knows that she wants to continue teaching Bio Accelerated until it’s “the best that it can be.” “I know that my classroom has lots of energy. I know that my classroom is welcoming. I know that my classroom focuses on people first. And I think that’s where I know for sure I am,” Soto said thoughtfully, looking off into the distance as if she was picturing each student in her mind.

***

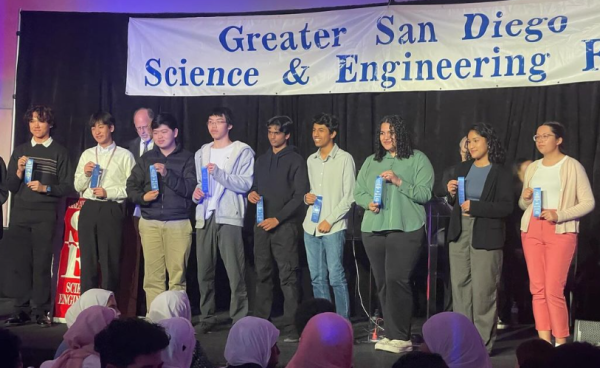

With such different backgrounds and dynamic characters, the Biology PLC could easily be a recipe for disaster. And yet students like seniors Sarah Del Olmo and Loren Rafael vouch that the program is one of the strongest on campus when comparing it to others like the Math and Language Departments.

So what’s the secret? How were these four teachers able to create such a unified, comprehensive program? As each explained independently, the reason for their success is that they are united by a common goal: to provide a quality education that prepares freshmen for the upper levels.

And with this shared mission as a baseline, each member contributes to their best ability to achieve it. Public school educator for 34 years and educational researcher specializing in developing strategies to create collaborative teaching environments, Richard DuFour, explains that it takes a culture of collaboration, where members “work together to analyze and improve their classroom practice,” to have a successful PLC.

Without a doubt, this commitment to collaboration certainly is achieved by the Biology PLC. Mardahl and Szakovits meet on Saturdays, unpaid, meticulously discussing ways that they can improve. Ekstein makes sure that content is accessible to all students, not just those who are high achieving. And Soto brings a fresh new perspective, trying to incorporate new technologies and ideas into lesson plans.

Like a family, there are unique, electric personalities within the group. Szakovits would describe it as Mardahl being like the mother, Ekstein as the cool aunt, and himself as the weird uncle. In reference to Ekstein, Mardahl said, “She’s my best friend, and I actually think of her as my little sister.” Their friendship extends beyond classroom walls, as Mardahl was there at both of Ekstein’s births and treats Ekstein’s children as her own nieces. Separately, Ekstein admitted, smiling, “I don’t want to say this, but she’s like my older sister.”

But at a deeper level, what makes this team a family is that every member acts on a duty to serve and sacrifice for one another. Older members act as mentors to newer additions. Szakovits, whose speaking style typically sounds jaded and succinct, reflected fondly on the impact that the Biology Accelerated PLC has had on him. Humbled, he acknowledged that it was Mardahl and Ekstein who had taught him how to be a good teacher—they modeled the values of being a quick grader, being entertaining to freshmen, and always maintaining a deep care for students. “ I feel like almost everything that’s good about me as a teacher was influenced by either one of them or the other, or both,” he admitted, speaking from the heart. Similarly, Soto looks up to her older peers as models of teaching and campus engagement. “ I’m learning not only how to be a better teacher, but also how to be helpful on campus. Ms. Ekstein works on projects to beautify campus. Dr. Mardahl always making sure everyone’s looked after. Mr. Szakovits is always willing to listen. It’s a great team,” she said smiling. “And sometimes I’m just listening. But they always make sure that I’m included in the conversation and I’m included in what the final product is.”

If any group of teachers were to be the model of collaboration, communication, and care, it would be the Biology Accelerated PLC. As Soto concluded, grinning from ear to ear, “I feel so honored to be in the room. It’s really an amazing PLC.”

I am a senior at Bonita Vista High. I’ve been on The Crusader’s staff for the last four years because I enjoy writing about breaking news and human...