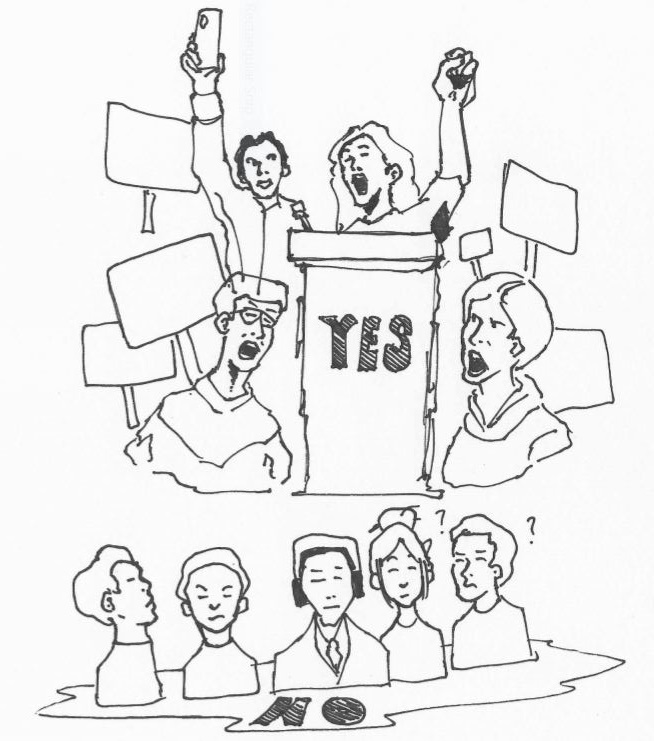

Yes vs No: Are student protests effective?

Yes.

By: Marcello Garbo

During the 2019-2020 school year, there have been multiple protests, regarding everything from global climate to the Sweetwater Union High School District’s (SUHSD) budget cuts. Those protests have been facilitated by Bonita Vista High (BVH), allowing students to go out and voice their opinions. However, in this form, protests are not as effective as they could be. Instead, if student protests were non compliant, they could incite the change that they seek.

Recently, a school-wide teacher protest was scheduled to take place on March 2, 2020. The time of the protest was deemed to be “inconvenient,” so it was rescheduled to March 6 during 6th period, when most students already left their classes. This detracted from the intended message of the protest, which in this case was advocating against the removal of teacher positions across the SUHSD. 60 percent of BVH students believe that teacher protests can be effective.

Outside of the SUHSD and throughout history, students have made meaningful change through protest — change that has lasted decades. In the 1960s, four African-American students from the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College staged a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter and refused to leave after being denied service. This action spurred other similar movements in the area and incited change in regards to the racial segregation that occurred in the time period.

An article published by the Harvard Ed. Magazine explains how students worldwide have been able to make a change by “localizing the argument,” to engage students and hold administrations accountable.

Anti-apartheid campaigns were most effective when they demanded universities to cut ties to support of racist policies in South Africa rather than marching directly against the U.S Government for supporting these policies.

Effective protests must also come with sacrifice, which protests at BVH simply don’t provide. School-organized protests lose their meaning since they allow students to leave the classroom without repercussion beyond a truancy. This enables students who may not be passionate about the issue to simply leave class. However, many passionate students voice their opinions during these protests, with 41 percent of students believing that they are effective.

62 percent of students at BVH have attended a protest, while 57 percent of those stated it was due to their passion for the issue.

Students who have been able to make significant change have put their education on the line. During the Vietnam War, over 10,000 Harvard students boycotted their Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) programs in an attempt to show Harvard that they opposed war sentiment. In response, Harvard significantly downgraded the ROTC. In this case, students risked suspension by declaring a strike.

One major concern that several opposers of student protests have is that students are not taken seriously. Fortunately, in more recent times, students have been able to talk to legislators in order to enact meaningful change.

An article by The New York Times describes the “Never Again” movement to combat gun violence after the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. As a result of the movement and the 187,000 students who experienced a shooting at their school, state lawmakers were able to persuade companies to cut ties with the National Rifle Association to decrease gun violence and increase regulation.

Additionally, the movement has garnered support from celebrities with millions of dollars in donations. Florida Governor Rick Scott has also agreed to meet with student survivors to discuss policy changes.

Historical precedent shows that if students are truly passionate about an issue and gain enough momentum to spread the word to the masses, then they have the ability to protest and make effective change. Although BVH’s numerous organized protests have attempted to spark changes at the SUHSD, a different approach could lead to the impacts many of the student body long for.

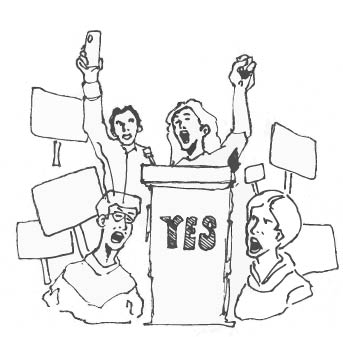

Students gather in the quad of Bonita Vista High (BVH) while others prepare to give a speech during sixth period on March 6. The walkout was organized against a district decision to eliminate 237 positions for the upcoming school year.

No.

By: Alexa Vazquez

Since the days of village witch hunts and torch-lit revolutions to the age of labor unions and political protests, people have always fought to let their voices be heard. It is the “right to assemble” given to us by the first amendment in the Constitution of the United States of America, allowing individuals to undergo the pursuit of justice against their perceived injustices.

Student-led protests are supposedly carried out with a similar intent. But however well-intended they may be, they are carried out without proper care and rarely result in any change, as those who attend have little interest in following up with further action to bring about the “necessary” change.

Limitless ambition to change the world may light the fire in students, but the reality of their situation may just as easily extinguish it. The goal in mind will seem farther out of reach when 15.4% of students at Bonita Vista High (BVH) attend these protests out of a desire to leave class, and have no overall interest in following up on the issue well after the protest.

In simpler words, they are ineffective and irritating to those who care deeply for the issue at hand.

Student-led protests justify hundreds of students to be outside of the classroom fraternizing about, rather than actually protesting. Some definitely take the process seriously, but the majority of time, these walkouts and strikes serve as a convenient excuse to skip class. About 62.8% of students attended BVH’s most recent protest opposing the elimination of 237 teachers in favor of district budget cuts. The end result of the protest was a cluster of students looking around in search of a purpose to the gathering, attending without any deeper knowledge on what it was that they were protesting against.

In an article published by The New Yorker, the author poses a question for the reader: “Are protests a productive use of our attention, or are they just a bit of social theater we perform to make ourselves feel virtuous, useful and in the right?” This becomes more of a valid question when taking into account the amount of students who attend protests out of a limited interest in the subject to feel as if they were making an impact. In that same article, the author describes protests as “more of a habit than a solution,” and that they “reduce the issue’s complexity so that it ignores the nature of problems in the modern world.”

Treating protests as simple informal social gatherings degrades the issue being discussed. Those students who do care for the issue are misrepresented and go unheard. By spreading word of a protest regarding an issue that is “simply” explained, one is downgrading the broader and more complex issue that passionate students are fighting against.

With the information behind some policies being so limited, protests have occurred to spite a decision that had already been decisively approved, such as the recent protest against the teacher layoffs. The protest occurred several days after the final decision had been reached by the Board of Trustees, and if those students who attended the protest were truly passionate about the subject, they would have attended this meeting themselves

Even when the existence of a protest is guaranteed, they most rarely result in further action in opposition to the policy. With 13.7% of students attending protests amidst following the footsteps of a friend, the issue being confronted may not matter to a majority of those attending. Thus, no further action is taken in the name of that crisis, rendering the protest almost useless.

According to an article published by The Atlantic, “Behind massive demonstrations, there is rarely a well-oiled and more-permanent organized party capable of following up on protesters’ demands and undertaking the complex, face-to-face and dull work that produces real change.”

Some may argue that student-led protests are important in sending a message to those with authority in regard to what’s being protested. However, accounts of protests from BVH’s past prove that this is not typically the case. If one truly desires to make a change, then it is necessary for that student population to be informed, and to find a solution to the problem for both the administrative and authoritative parties. Whatever that solution may be, it does not involve student protests.

Although freedom of speech allows for the student population to speak their minds on issues plaguing the BVH campus today, They most often than not amount to nothing other than a large gathering of misinformed people and a population of passionate students unsatisfied with how their voice was represented. The goal of protests should be to create meaningful change, unfortunately, this change is not often met.

I am a freshman for the 2018-2019 Bonita Vista High School’s Crusader publication. It is my first year on staff, and the experiences it has offered have...

Writing can be a ridiculously painful thing to endure, but I think that giving it up would be even worse. After all, who doesn’t like a challenge? I’m...

Hello! My name is Noah Nafarrete, and I am the current Arts and Cultures section editor for The Crusader. This is my second year on staff. I have a profound...

I am a senior at Bonita Vista High (BVH) and this is my third year on staff. In previous years, I was working as a staff writer. This year, I am one...